Published on March 15, 2025

Ever wonder why a litre of milk in Canada costs $1.50-$2.00 while Americans pay roughly $0.80 USD (about $1.08 CAD)? Or why Canadian cheese prices make you consider lactose intolerance as a financial strategy?

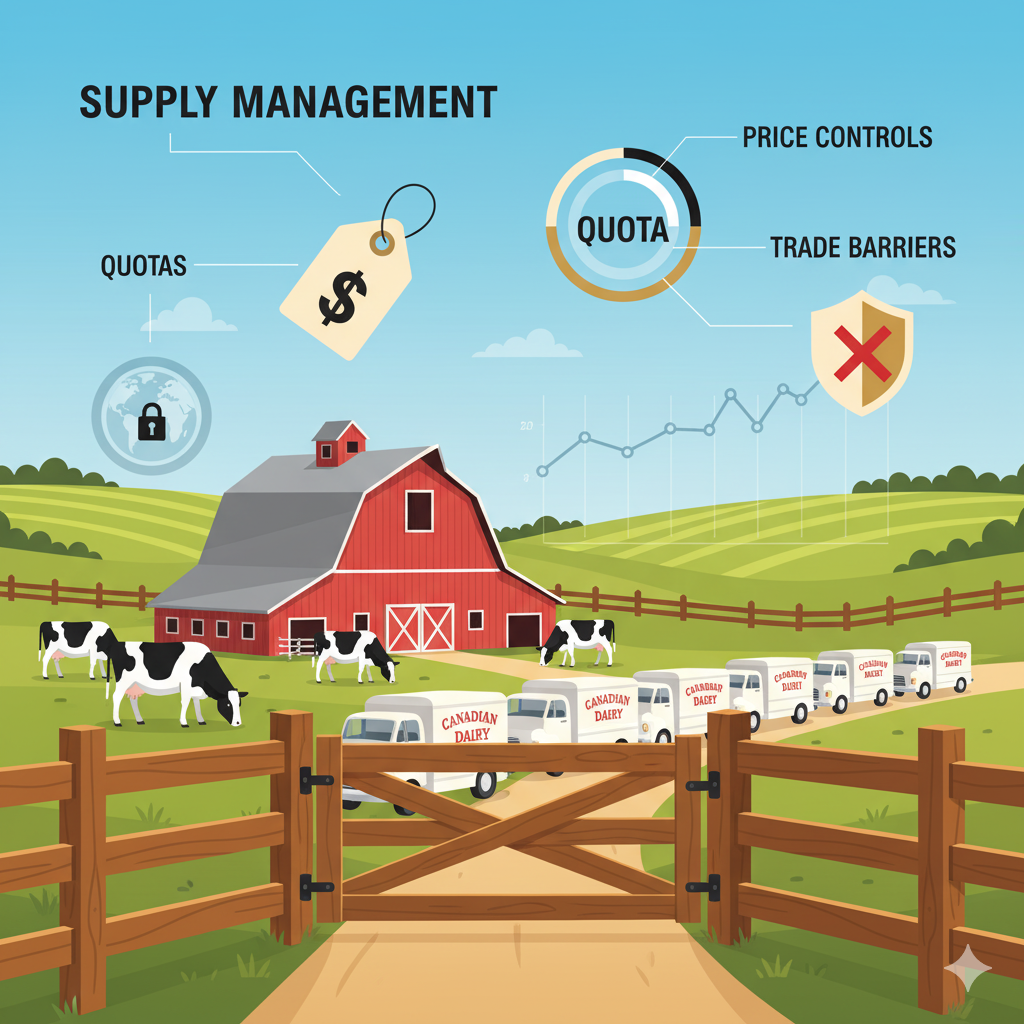

Welcome to supply management—Canada's most controversial agricultural policy, where the government controls production quotas, sets minimum prices, and restricts imports for dairy, eggs, and poultry. It's a system that ensures farmers earn stable incomes while consumers pay premium prices, creating economic winners and losers in ways that might surprise you.

The Basic Economics

Supply management operates on three pillars: production quotas, price controls, and import restrictions. Unlike most agricultural sectors where prices fluctuate with market conditions, supply management creates artificial scarcity to maintain stable, elevated prices¹.

Here's how it works in practice. The Canadian Dairy Commission determines how much milk the country needs, then allocates production quotas to provinces and individual farms². Farmers can only produce what their quota allows, creating scarcity that supports higher prices.

Meanwhile, import tariffs of 200-300% on dairy products ensure foreign competition can't undercut Canadian prices³. A block of cheese that costs $8 in the US faces tariffs that push the Canadian retail price to $15-$20.

The system covers dairy ($15.2 billion annually), eggs ($1.4 billion), chicken ($3.1 billion), and turkey ($544 million)⁴. Combined, these sectors represent roughly $20 billion in annual production—about 25% of total Canadian farm receipts.

The Historical Context

Supply management emerged from the agricultural chaos of the 1960s and early 1970s. Dairy farmers faced volatile prices that swung from profitable to ruinous within months. Many family farms went bankrupt during price collapses, while consumers faced shortages when production dropped⁵.

The federal government initially tried direct subsidies and price supports, but these proved expensive and politically unsustainable. Supply management offered an alternative: instead of taxpayers supporting farmers through subsidies, consumers would support farmers through higher prices.

The system launched in 1972 for eggs, expanded to chicken in 1978, and encompassed dairy by 1979⁶. For over four decades, it has delivered on its primary promise: stable farm incomes and predictable food supplies.

The Cost to Consumers

Canadian families pay significantly more for supply-managed products than they would in a free market. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Canadian dairy prices are roughly 50-60% higher than world market prices⁷.

For a typical family spending $200 monthly on dairy, eggs, and poultry, supply management adds approximately $60-$80 to their grocery bill⁸. That's $720-$960 annually—roughly equivalent to a week's wages for a minimum-wage worker.

The burden falls disproportionately on lower-income families who spend larger portions of their income on food. Statistics Canada data shows that the bottom income quintile spends 16% of their income on food, compared to 9% for the top quintile⁹. Supply management's price premiums therefore function as a regressive tax.

Regional variations compound the inequality. Northern and remote communities already face elevated food costs due to transportation expenses. Supply management's price floors add another layer of expense for populations least able to afford it.

The Farmer Perspective

From producers' viewpoint, supply management provides economic security unavailable in most agricultural sectors. Dairy farmers know they can sell their milk at predictable prices, enabling long-term planning and investment decisions.

The system has created substantial wealth for quota holders. Dairy quotas trade for approximately $40,000 per cow¹⁰. A typical Ontario dairy farm might hold quotas worth $3-5 million—often representing more wealth than the land and equipment combined.

This quota value provides retirement security for farmers and collateral for bank loans. When farmers retire, they sell their quotas to younger producers, creating a transfer payment system within the agricultural sector.

However, quota costs create barriers for new farmers. Young people wanting to start dairy operations face capital requirements of $5-8 million, compared to $1-2 million for comparable operations in countries without supply management¹¹.

The International Trade Complications

Supply management creates ongoing friction in international trade negotiations. The United States, European Union, and other trading partners consistently pressure Canada to dismantle or modify the system¹².

The Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations nearly collapsed over dairy access. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement required Canada to provide additional dairy market access, effectively creating small cracks in the supply management wall¹³.

New Zealand, Australia, and European dairy exporters argue that Canadian supply management violates World Trade Organization principles by restricting market access. Canada defends the system as a legitimate domestic agricultural policy¹⁴.

These trade tensions have real economic costs. Other countries sometimes retaliate against Canadian exports in different sectors, affecting industries with no connection to supply management.

The Economic Efficiency Question

Economists generally criticize supply management as economically inefficient. The system encourages overproduction of inputs (like expensive barns and equipment) while restricting output, leading to higher costs per unit of production¹⁵.

Canadian dairy productivity lags behind countries with competitive markets. According to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canadian dairy farms average 76 cows per farm, compared to 337 in the United States¹⁶. Smaller scale operations typically have higher per-unit costs.

The Conference Board of Canada estimated that eliminating supply management could reduce consumer costs by $2.6-3.8 billion annually while increasing economic efficiency¹⁷. However, these savings would come at the cost of farm incomes and rural economic stability.

The Innovation Impact

Supply management affects agricultural innovation in complex ways. Guaranteed prices reduce incentives for cost-cutting innovations, potentially slowing productivity growth. Why invest in efficiency improvements when you can pass costs to consumers through higher prices?

However, stable incomes enable long-term investments in new technology, animal genetics, and sustainable practices. Many Canadian dairy farms feature advanced automation and environmental controls that wouldn't be financially viable under volatile pricing¹⁸.

The system also supports agricultural research and development through producer levy programs. Dairy farmers contribute approximately $30 million annually to research through Dairy Farmers of Canada¹⁹.

The Rural Community Effects

Supply management significantly impacts rural Canadian communities. The system supports approximately 220,000 jobs directly and indirectly, with many concentrated in rural areas²⁰.

Small dairy processing plants that might not survive import competition operate throughout rural Canada, providing local employment and economic diversification. Towns like Ingersoll, Ontario, and Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec, built substantial food processing sectors around supply-managed agriculture²¹.

However, quota concentration threatens some rural communities. As farms consolidate and quotas migrate toward larger operations near urban centers, smaller rural communities lose dairy farms and associated economic activity.

The Environmental Considerations

Supply management's environmental impacts are mixed. Stable pricing enables investments in environmental technologies like methane digesters and improved manure management systems. Many Canadian dairy farms exceed environmental standards²².

However, import restrictions may increase global greenhouse gas emissions if Canadian production is less efficient than foreign alternatives. Importing dairy products from highly efficient operations might generate fewer emissions than producing them domestically²³.

The system also affects land use patterns. Quotas tie production to specific locations, potentially preventing the most environmentally suitable regions from expanding production.

The Food Security Argument

Supporters argue that supply management enhances Canadian food security by maintaining domestic production capacity. Unlike sectors dependent on imports, supply-managed products remain available during international disruptions.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated some supply chain vulnerabilities, though essential food items like dairy remained readily available throughout the crisis²⁴. However, critics note that food security could be maintained through strategic reserves rather than permanent price premiums.

The food security argument becomes more compelling in the context of climate change and potential future supply disruptions. Maintaining domestic production capacity provides insurance against international market volatility.

The Political Economy Reality

Supply management enjoys strong political support in Quebec and Ontario, provinces that together elect 199 of 338 federal MPs²⁵. Rural ridings with significant agricultural populations wield disproportionate political influence through Canada's electoral system.

The system also benefits from concentrated benefits and diffuse costs. Farmers receive large, visible benefits, while consumers face small, invisible costs spread across millions of households. This creates powerful lobbying for the system and weak opposition.

Major political parties have generally supported supply management, though with varying degrees of enthusiasm. The Conservative Party faced internal divisions on the issue during recent trade negotiations²⁶.

The Reform Options

Various reform proposals have emerged over the decades, ranging from gradual liberalization to complete elimination. Options include:

Quota buyouts: Government purchases existing quotas and eliminates the system, compensating farmers for lost wealth while reducing consumer prices.

Gradual phase-out: Slowly increasing imports and reducing price supports over 10-15 years, allowing adjustment time for farmers and consumers.

Partial reform: Maintaining supply management for some products while liberalizing others, or allowing limited competition within quota systems.

International compromise: Providing additional market access to trading partners while maintaining core supply management principles.

Each approach involves different economic trade-offs between consumer costs, farmer incomes, and international relations.

The Bottom Line

Supply management represents a fundamental choice about agricultural policy priorities. The system successfully delivers stable farm incomes and predictable food supplies, but at the cost of higher consumer prices and reduced economic efficiency.

For Canadian consumers, supply management means paying $700-$1,000 annually more for dairy, eggs, and poultry than they would under free market conditions. For farmers in these sectors, it means economic security and substantial quota wealth that wouldn't exist under market pricing.

The policy creates clear winners and losers. Rural communities benefit from stable agricultural employment, while urban consumers pay premium prices. Existing farmers gain quota wealth, while aspiring farmers face high entry barriers.

Whether supply management represents good public policy depends largely on your priorities. If you value agricultural stability, rural employment, and food security above consumer savings and economic efficiency, the system delivers substantial benefits.

If you prioritize affordability, free market competition, and international trade relations, supply management appears costly and outdated.

Understanding these trade-offs helps evaluate political promises and policy proposals around agricultural policy. The debate isn't really about the economics of milk prices—it's about what kind of agricultural sector and rural economy Canada wants to maintain.

The next time you're paying $7 for a block of cheese, remember you're not just buying dairy products. You're supporting a complex agricultural policy that prioritizes farm stability over consumer savings, rural employment over urban affordability, and domestic production over international trade.

Whether that's a good deal depends on your perspective. But at least now you know what you're actually paying for.

References

Agricultural Policy and Economics:

[1] Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. "Supply Management in Canada." 2024.

[2] Canadian Dairy Commission. "Annual Report 2023-24." 2024.

[3] Global Affairs Canada. "Canada's Supply Management System." 2024.

[4] Statistics Canada. "Farm product prices, crops and livestock." Table 32-10-0077-01. 2024.

[5] Canadian Federation of Agriculture. "History of Agricultural Policy in Canada." 2023.

[6] Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. "Evolution of Supply Management in Canada." 2023.

[7] OECD. "Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2024: Canada." 2024.

[8] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. "The Cost of Supply Management to Canadian Families." 2023.

[9] Statistics Canada. "Household spending, Canada, regions and provinces." Table 11-10-0222-01. 2024.

[10] Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. "Dairy Quota Values by Province 2024." 2024.

[11] Dairy Farmers of Canada. "Getting Started in Dairy Farming." 2024.

[12] Global Affairs Canada. "Canada-United States Trade Relations: Agriculture." 2024.

[13] Global Affairs Canada. "Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement: Agricultural Provisions." 2020.

[14] World Trade Organization. "Trade Policy Review: Canada 2023." 2023.

[15] C.D. Howe Institute. "The Economic Costs of Supply Management." Commentary 595. 2023.

[16] Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. "Statistical Overview of the Canadian Dairy Industry 2023." 2024.

[17] Conference Board of Canada. "Economic Impact of Dairy Liberalization in Canada." 2022.

[18] Dairy Research Cluster. "Innovation in Canadian Dairy Farming." 2023.

[19] Dairy Farmers of Canada. "Research and Development Investments." 2024.

[20] Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. "Employment in Supply Managed Sectors." 2023.

[21] Statistics Canada. "Food manufacturing in Canada." 2024.

[22] Environment and Climate Change Canada. "Environmental Performance of Canadian Agriculture." 2023.

[23] Conference Board of Canada. "Climate Change and Canadian Agriculture." 2023.

[24] Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. "Food Security during COVID-19." 2021.

[25] Elections Canada. "Electoral Districts by Province/Territory." 2024.

[26] MacDonald-Laurier Institute. "Conservative Party Policy on Supply Management." 2023.